A Legacy Begins in Georgia

From Tarvin, England, my great-great-great-grandfather eventually settled in Georgia. In the 1830s, with the help of a dozen men, he dug a “big hole” in search of gold.

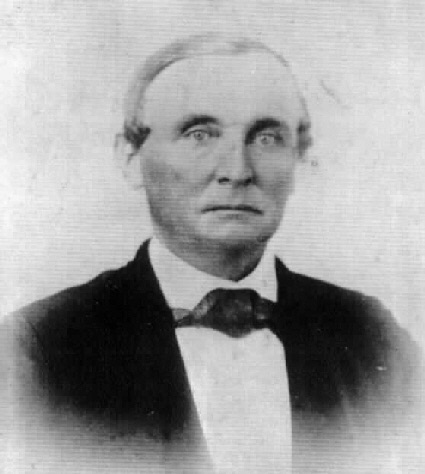

Long before the California gold rush, gold was discovered in Cherokee country—specifically, middle Georgia. After arriving in the U.S., John Hockenhull made his way south and acquired the Battle Branch Mine. Hoping to strike it rich, he and his team dug a massive, fruitless hole.

Striking Gold Against All Odds

Nearly broke, Hockenhull released his men, promising to pay their back wages someday. All but one, John Pasco, left.

Then, like something out of a movie, Hockenhull and Pasco struck gold. On that first day, they found nuggets the size of peas and acorns. The Battle Branch Mine became the richest in the state. In a moment, my grandfather went from nearly bankrupt to wealthy.

From Gold to Bricks—Built by Slaves

With his fortune, Hockenhull entered the brick-making business. As was common at the time, he used enslaved labor—up to two dozen individuals by some estimates.

He used his bricks to build the first brick home in Dawson County, Georgia. More significantly, the bricks made by his slaves were used to construct the Dawson County courthouse in 1858. That courthouse still stands today.

Remembering the Past

Years ago, my sister and I visited it—along with our grandfather’s grave. We couldn’t visit his home; the land is now owned by the Department of Defense.

When the Civil War broke out, Hockenhull joined the Confederacy, earning the rank of Major due to his status and business experience. He survived the war and died in 1880 at age 68.

Why Share This?

So why share this story? Am I ashamed? Trying to erase guilt? Not at all. I haven’t benefited from my ancestor’s sins, nor do I carry his guilt.

But slavery hasn’t disappeared. It just moved.

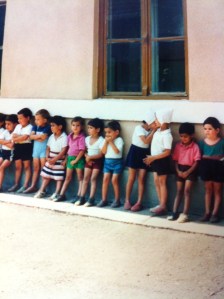

Modern Slavery in Pakistan

Today, in the brick kilns of Pakistan, entire families—men, women, and children—are trapped in generational debt slavery, making bricks in inhumane conditions.

Here’s the painful irony: in 1858, my grandfather sold bricks for $8 per 1,000. That’s around $300–$500 today. In 2025, in Pakistan, 1,000 bricks sell for just $6.

Six. Dollars.

Some try to justify American slavery by claiming slaves were “treated well.” That’s a lie. Yet, having seen it firsthand, I can say that modern-day brick kiln workers often endure even worse conditions.

What We Can Do Now

That’s where we come in.

Through the incredible work of Grace Charity School in Toba Tek Singh, and Redeeming Love Missions—our nonprofit ministry at [Redeem.Love](https://redeem.love)—we’re rescuing entire families from modern-day slavery and giving their children a chance at education and dignity.

Instead of arguing over reparations, why not make a real difference for real slaves—right now?

Go to [Redeem.Love](https://redeem.love) and give whatever you can. We can’t change the past—but we can help change the future.